Mugwort

A hedge of mugwort protecting our field on an early summer morning.

Most likely you have come across mugwort, for it grows everywhere: in the cracks of city pavement, along sooty expressways, in parks and meadows and abandoned lots. But perhaps you have not noticed it. I didn’t until the summer of 2020.

We had just moved to the Hudson Valley, and I wanted to transplant some tomatoes and zucchini I’d dug up from our garden in New Hampshire. The realtor had mentioned that our new house came with a couple of raised beds, but all I saw by the garden shed, where these beds supposedly were, was an intimidating thicket that was blithely ignoring and obscuring a rickety garden fence. According to my herb books, it was mugwort. The stalks towered a foot or two over my head, sending out branches shaggy with deep lobed, silver bottomed leaves. I pulled at the base of one. To my surprise, it popped right out. I pulled out another and entered into the thicket. As I brushed against the leaves, they released an aroma reminiscent of sage and creosote—and something else I could not name.

A few hours later, after having accumulated an enormous pile of stalks, leaves and nubby rhizomes, I had uncovered the beds. Normally, I would have felt worn out by all the pulling, yanking and dragging, but I was in a calm, dreamy state of mind. I wondered if my unusual mood had to do with that beguiling scent.

Noodling around online, I found out that people smoke mugwort for its relaxing and mildly hallucinogenic properties. And that’s not all I learned. It turns out mugwort has been revered in cultures throughout the world for its medicinal and magical properties. Stories abound. Here are some favorites: Mugwort was the first of the Anglo Saxon’s Nine Sacred Herbs and was mentioned in Chinese medical texts predating the common era. It was planted by Roman roadsides as its leaves, placed between the sole of the foot and the sandal, soothed weary travelers (I tried this, to good results). St. John the Baptist fashioned a girdle of it to protect him in the wilderness. In Europe and Asia, sprigs were hung over doors to keep out evil spirits; in the Americas, Aztecs made an incense from it. It’s also tasty, though bitter, used to flavor German geese and Japanese mochi, and was a prime ingredient in beer before hops became more popular. Hence its name: mug invoking a mug of beer, and wort being the old English word for plant.

Not everyone loves it, of course. It figures prominently on invasive species lists. Farmers and gardeners get exasperated by its tendency to pop up unasked, spread quickly, and refuse to leave. True to form, the vegetable beds I cleared in 2020 had been reclaimed by the mugwort thicket in 2021. But by this time I’d fallen in love and didn’t mind at all.

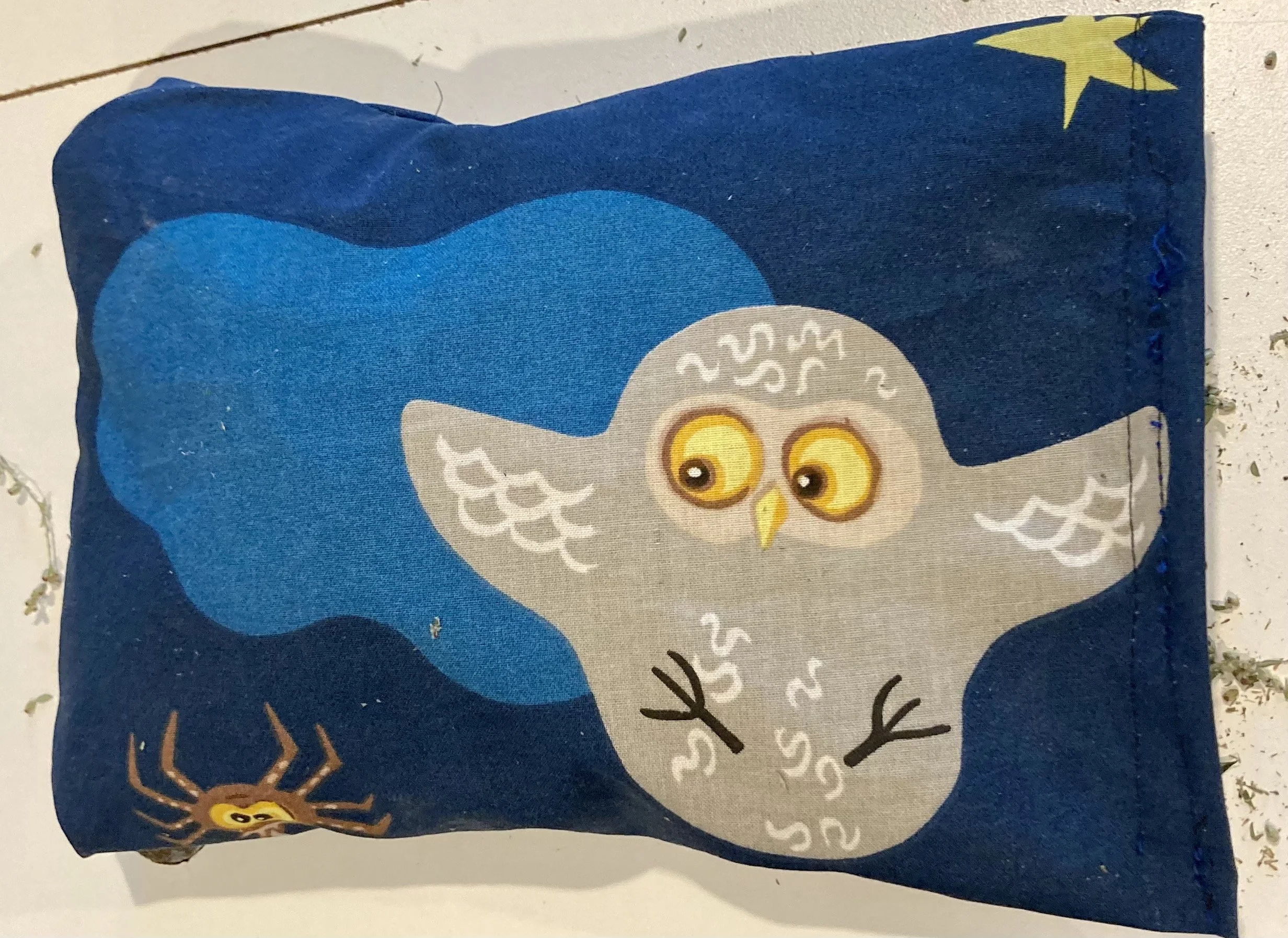

Here are some pictures of our Tuesday group making mugwort/sweet annie dream pillows. We are experimenting to see if sleeping with them makes for more lucid dreaming….